Jul 29, 2020

Wasn’t Kurt Cobain’s suicide a wakeup call? TSN’s Michael Landsberg knows how to talk about mental health issues. And on what would have been Robin Williams’ 69th birthday, the geeks speak about a topic that seems to have been largely swept under the rug by the entertainment industry.

Robin Williams’ passing got us talking

The entertainment industry can be all flashy lights, glitter, limousines, and big homes. It could also be a dark, lonely, and depressing spot to be in. The stories of celebrities taking their own lives have been sadly common in the past few years. It’s sad to think that our larger than life favourites weren’t as happy as we thought. Let’s take Robin Williams – who would’ve turned 69 this week – as an example. After Williams died, we cried, laughed, and mourned. The reality set in and we were confused. How can arguably one of the most naturally gifted comics of all time take his own life?

This unexpected bombshell lit the helplines up like Patch Adams’ red nose. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline saw a surge in callers. The loss of Williams had everyone reeling. Soon after his passing it was revealed that Williams had Parkinson’s disease. Scratch that – Robin Williams had Lewy Body Dementia.

He was drifting away

Williams’ widow, Susan Schneider Williams, published an article called “The terrorist inside my husband’s brain” in the journal Neurology. She wrote about the joy of their relationship and she notes that many months before he died, Robin was under the care of doctors for many of symptoms including gastrointestinal problems, insomnia, and a tremor. He was treated with both psychotherapy and psychotropic medications. He went to Stanford for hypnosis to treat his anxiety. He exercised with a physical trainer. His voice weakened, left hand tremor was continuous and he had a slow, shuffling gait. He was beginning to have trouble with visual and spatial abilities in the way of judging distance and depth. His loss of basic reasoning just added to his growing confusion.

The very complicated question

In the article “Lessons On Depression From The Life Of A Beloved Celebrity” by Steven Schlozman, M.D. he answered the question of why Robin would take his own life.

“This is, of course, a great and very complicated question”.

“It’s not a great question because it’s perplexing; it’s a great question because it reminds us all that we are vulnerable to all sorts of diseases, and that these diseases sometimes win. Would the question be as potent if it concerned a different celebrity’s battle with cancer? Probably not, but it ought to be. Cancer, depression, substance use disorders…these are all diseases. They all have proven treatments, and we as a society need to remember that,” he wrote.

“We also, however, need to remember that sometimes the disease wins. Whether the disease wins or not is not tied to talent or fortune; it is tied to the unique vulnerabilities of the individual and the disease from which he or she suffers.” Schlozman concluded, “We are all human, no matter how beautiful, rich or talented. We all have our histories, our vulnerabilities and our illnesses.”

Mental health in the entertainment industry outside of North America

While names like Williams, Anthony Bourdain and Avicii are some of the latest names to fall to their demons, mental health isn’t just a thing in the North American entertainment industry.

Back in June, Sushant Singh Rajput, a 34-year old Bollywood actor that stunned fans in several top-drawing films, died by suicide. Rajput was found dead at his residence in Mumbai. Reports confirmed that he allegedly suffered from clinical depression because of a professional rivalry. Several of the actor’s friends in the industry spoke out about his struggles to make it. Others are pointing their fingers to the closed culture in Bollywood.

“I knew the pain you were going through. I knew the story of the people who let you down so bad that you used to weep on my shoulder,” Shekhar Kapur, who was supposed to direct Rajput in a film that was eventually shelved, wrote in a tweet soon after the passing.

In a separate tweet, actress Swara Bhasker called accusations against Bollywood personalities “the height of idiocy.”

“We don’t know what he (Rajput) went thru. We don’t know the cause. STOP taking out your frustration using the pain of a troubled person… Let him have his peace & his family privacy,” she tweeted.

Korea’s entertainment industry does some soul searching

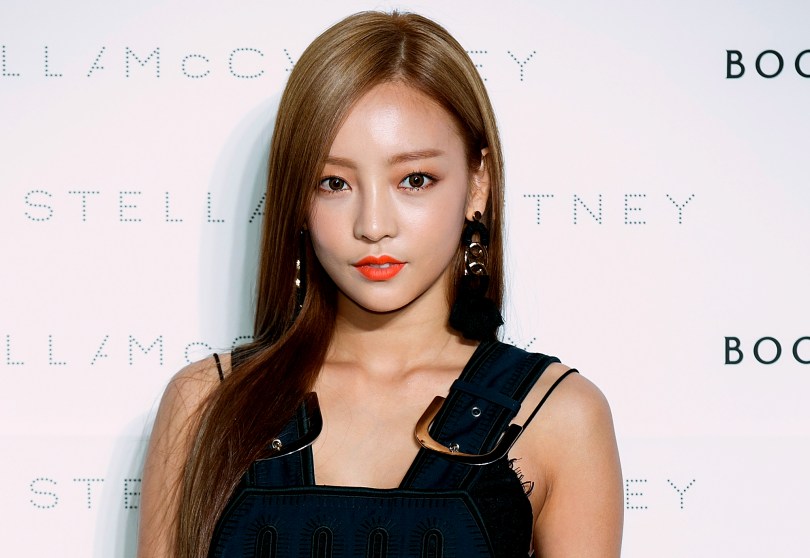

From Bollywood to the K-pop music scene. Two beloved female

stars, Sulli and Goo Hara, ended their own lives in two months,

exposing the painful side of being a K-pop idol.

The K-pop phenomenon gets dismantled largely through social media. Their stars are exposed to both a flood of fan letters and hurtful comments and cyberbullying on everything from their looks to their singing skills to their private lives.

“From an early age, they live a mechanical life, going through a spartan training regimen,” said Lee Hark-joon, a South Korean journalist who has produced a TV documentary on the making of a K-pop girl group and co-wrote the book K-pop Idols: Popular Culture and the Emergence of the Korean Music Industry. “They seldom have a chance to develop a normal school life or normal social relationships as their peers do.”

“Their fall can be as sudden and as dramatic as their rise to the height of fame,” and all at a young age, Hark-joon added. “Theirs is a profession especially vulnerable to psychological distress — they are scrutinized on social media around the clock, and fake news about their private lives is spread instantly.”

Sleep tight

Goo was a former member of K-pop group, Kara. She had struggled with online abuse. The trolls spread rumours about her looks and how she had gone under the knife. Things got worse when she booked up with her boyfriend. More rumours spread that the two had a sex video.

“I won’t be lenient on these vicious commentaries any more,” Goo wrote on her Instagram complaining about her mental health and depression.

“Public entertainers like myself don’t have it easy — we have our private lives more scrutinized than anyone else and we suffer the kind of pain we cannot even discuss with our family and friends,” she said. “Can you please ask yourself what kind of person you are before you post a vicious comment online?”

Goo’s suicide prompted a number of people who supported an online petition to the office of President Moon Jae-in asking for harsher punishment for sexual harassment. The petition more than doubled to 217,000 since her suicide was reported.

In her last Instagram message, Goo uploaded a photo of her lying on her bed. She wrote “Jalja,” which is translated to, “sleep tight.”

Is Hollywood doing enough?

In 2017, the U.S rate was 14 per 100,000 people, up 33 percent from 1999. Suicide is now the second leading cause of death for people aged 10 to 35. That’s right, as young as 10. According to the CDC, the highest female suicide rate from 2012 to 2015 occurred in the combined fields of arts, design, entertainment, sports and media. The World Health Organization states that around one in four people will be affected by mental or neurological disorders at some point in their lives.

UTA board member Tracey Jacobs tells us, “The pressure to perform, coupled with the intense proliferation of social media and the 24-hour news cycle, has affected young people in a way that many of my peers did not experience in their careers. Those factors can be overwhelming and often toxic.”

L.A.-based psychotherapist Ira Israel, author of the book How to Survive Your Childhood Now That You’re an Adult, believes that anxiety and depression are especially prevalent in entertainment “because the stakes are so high. The industry attracts highly competitive people who believe they are playing a zero-sum game, and the spoils of war — cars, homes, offices — are excessively conspicuous. The power games and exploitation in Hollywood foment countless afflictions and addictions.”

Euphoria is one of the few shows that talks about mental health

Hollywood is doing better at using mental health as part of show storylines. There’s 13 Reasons Why. Other shows like ABC’s Million Little Things, HBO’s Euphoria centre around a tale of mental health. But within Hollywood, companies haven’t offered much beyond the basics — typically three free counselling sessions through an Employee Assistance Program (EAP). Some have upped the benefit, including Hulu that offers six free in-person sessions per year. Over at Netflix, they get eight. NBC/Universal gives out ten.

But the severity of the issues seems to be awakening Hollywood. The fact that it needs to do more in its own ranks, especially given that these are businesses where the most precious capital is brain power. “Mental health should be a priority for all of us,” says Mandeville Films’ David Hoberman, who suffered from OCD and depression in his childhood. “We need to do anything we can in Hollywood to discuss it and create exposure.” Adds Jacobs: “I’ve experienced mental health issues within my own family and have seen the pain and devastation it causes. Like cancer, mental illness is a serious disease that needs to be treated. Unfortunately, there’s still a stigma.”

The post Mental Health and the Entertainment Industry with TSN’s Michael Landsberg appeared first on The Geeks and Beats Podcast with Alan Cross and Michael Hainsworth.